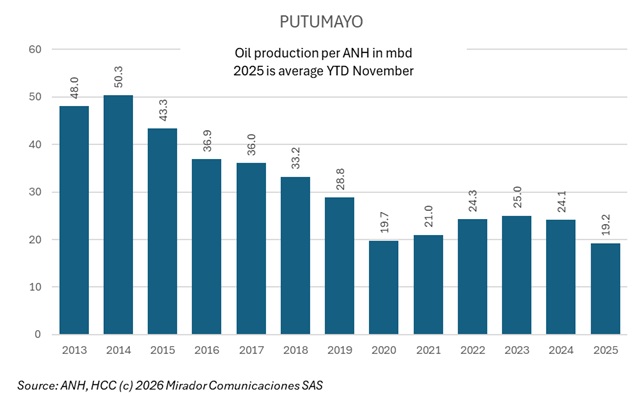

Ecuador’s decision to raise crude transport tariffs through its Trans-Ecuadorian Pipeline System (SOTE) from US$3 to US$30 per barrel—a 900% increase—has forced Colombian oil companies to evaluate costly alternatives for evacuating production from southern Putumayo department.

Guyana’s petroleum boom transformed the South American nation of 800,000 inhabitants into the world’s largest per capita oil producer and Latin America’s fastest-growing economy.

Pablo Yesid Fajardo Benítez has been nominated to replace Orlando Velandia as president of Colombia’s National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH), following Velandia’s resignation.

Venezuela’s National Assembly approved initial legislation Thursday reforming the country’s hydrocarbon law to attract foreign investment following Delcy Rodríguez’s assumption of power after U.S. forces deposed Nicolás Maduro on January 3.

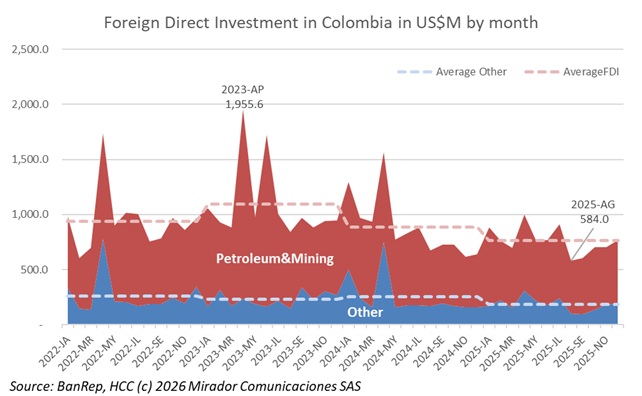

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Colombia totaled US$9.174 billion in 2025, representing a 14.1% decline from US$10.682 billion in 2024, according to Banco de la República data.

Ecuador announced plans to increase tariffs for transporting Colombian crude oil through its OCP pipeline, escalating commercial tensions between the neighboring Andean nations. E&Ps operating in the Putumayo use the OCP to get their crude to export.

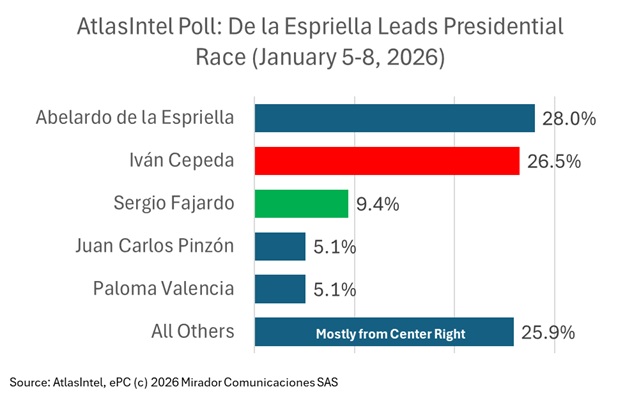

A new GAD3 poll revealed by Noticias RCN shows Iván Cepeda (Pacto Histórico) leading Colombia’s presidential race with 30% voter intention, followed by Abelardo de la Espriella (Defensores de la Patria) at 22%, and Paloma Valencia (Centro Democrático) at 3%. The survey of 1,207 respondents carries a 2.83% margin of error.

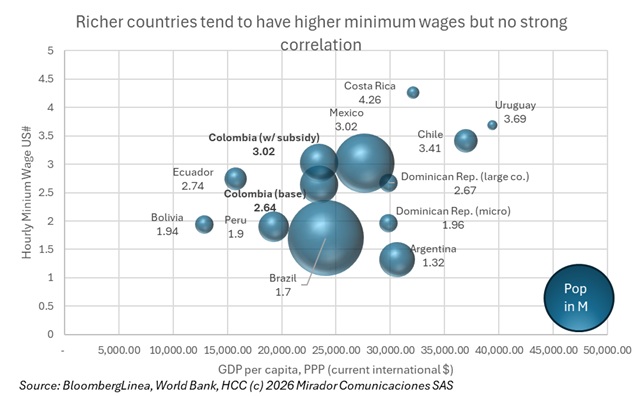

Costa Rica, Uruguay, and Chile continue leading Latin America with the highest hourly labor costs based on 2026 minimum wage rates. The analysis assumes a standard workday of 8 hours daily and 22 working days monthly, though this may differ from legal calculations in each country.

President Gustavo Petro ordered the National Legal Defense Agency (Andje) to recover property from the SPEC regasification plant in Cartagena, claiming it represents an unconstitutional private monopoly that substantially raises electricity tariffs.

An AtlasIntel poll (sponsored by Revista Semana) conducted January 5-8, 2026, reveals Abelardo de la Espriella leading Colombia’s presidential race with 28% voter intention, narrowly ahead of Iván Cepeda at 26.5%. The survey of 4,520 participants carries a 1% margin of error for general results and 3% for party consultations, with 95% confidence level. UPDATED Bottom-Line.